The present day Benin was occupied by several kingdoms.

The most prominent were called Danhomé (Abomey), Xogbonou (Porto-Novo), Allada, Nikki, Kouandé, Kandi.

The first rulers of Abomey and Porto-Novo came from the Adja-Fon migration, which came from neighbouring Togo (Tado). The other peoples came from present-day Nigeria, Niger and Burkina Faso.

Thus, the country was once a hotbed of ancient and brilliant civilizations, built around these kingdoms: city-states.

They had developed a local trade, based from the seventeenth century on the slave trade, then on the oil palm trade after the abolition of the slave trade in 1807.

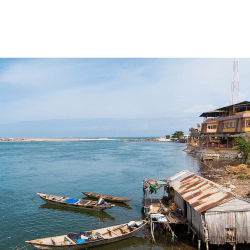

This trading economy encouraged the establishment of trading posts along the coast (“Slave Coast”) controlled by the English, Danes, Portuguese and some French.

In 1704, France was allowed to build a port at Ouidah while in 1752, the Portuguese discovered Porto-Novo.

In 1863, the first French protectorate was established with King Toffa of Porto-Novo who sought help against the pretensions of the King of Abomey and attacks by the British established in Lagos.

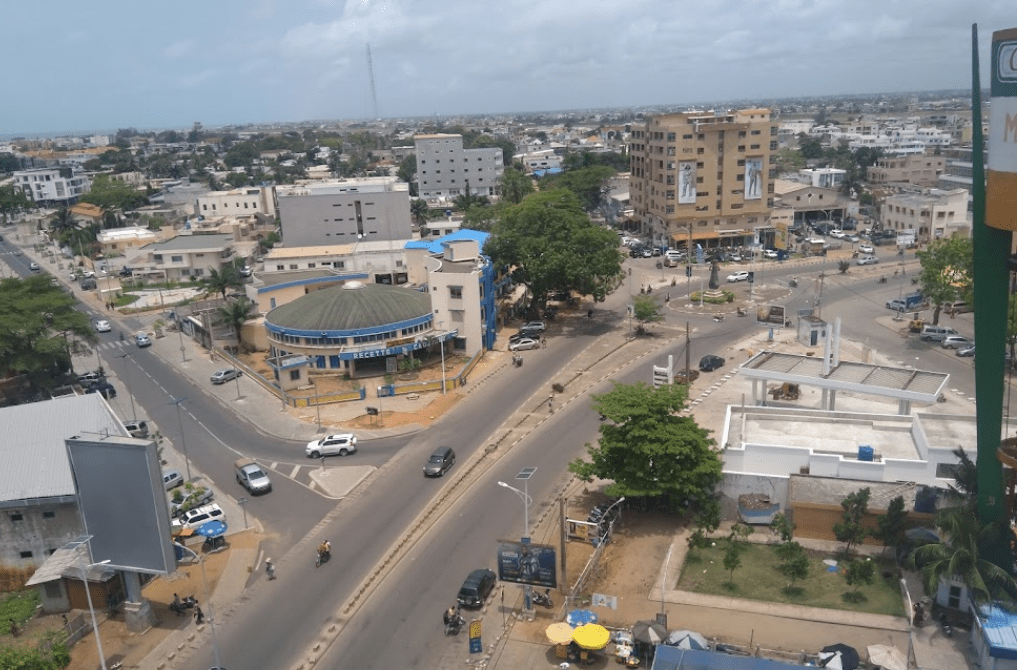

In the same year, Glèlè, king of Abomey, authorized the French to settle in Cotonou. In 1882, the sovereign of the kingdom of Porto-Novo signed a new protectorate agreement with France who sent a “French resident” to assist the king.

In 1894, the French, victorious over the local kings, created the colony of Dahomey and dependencies. The territory took the name of the most prominent kingdom and the most resistant to foreign occupation: Danhomé with its legendary king Behanzin.

Proclaimed a Republic on 4 December 1958, Benin acceded to international sovereignty on 1 August 1960, under the name of Dahomey.

Several presidential, legislative and local elections have sanctioned the devolution of political power. In fifteen years, political liberalism has generated three alternations at the top of the state.

It has experienced two waves of democratization, crowned by elections from which the rulers have come.

The first dates back to the dawn of independence with the general elections of December 1960.

This period was marked by the incomplete term of office of the President of the Republic, who was swept away by a military coup d’état in 1963.

In addition, political life suffered from monolithism, as very quickly the new president inspired the merger of political parties into a single official: the Dahomean Unity Party (PDU).

The second wave of democratization has been underway since February 1990. Its specificity is that it is long-term and allows for the stability of democratic institutions.

Generally, the country’s contemporary political history can be divided into three major periods: the period of political instability, the military-Marxist period, and the period of democratic renewal.

The first twelve years of independence were marked by political instability.

A series of coups d’état followed one another until 1970. The founding act of this instability was the putsch of Colonel Christophe Soglo who overthrew Hubert Maga, the father of independence, democratically elected on 28 October 1963.

With the new Constitution adopted in November 1960, the general elections, held on 11 December 1960, confirmed Hubert Maga’s continued presence in power. But taking advantage of the social unrest in the country, the army took power in 1963. Three months later, the administration of the country was entrusted to a civilian government.

Sourou Migan Apithy became President of the Republic and Justin Ahomadégbé his Prime Minister and Vice-President. A new Constitution was adopted by referendum on 5 January 1964. But these two government leaders couldn’t get their violins in tune. On December 1, 1965, the army forced them to resign. However, civilians retained power. It fell to the President of the National Assembly, Taïrou Congacou. Dissatisfied with his governance, Christophe Soglo, who had become a general, once again propelled the army to the forefront.

On December 22, 1965, he proclaimed himself de facto President of the Republic. He was overthrown by the young military officers on December 17, 1967. Three days later, Commander Maurice Kouandété, the mastermind of the coup d’état, entrusted the destiny of the country to the head of the Army, Lieutenant-Colonel Alphonse Alley.

In May 1968, presidential elections were organized by the officers in order to hand over the sceptre of Dahomey once again to a civilian authority. However, the country’s three traditional political leaders, Hubert Maga, Sourou Migan Apithy and Justin Ahomadégbé, are not allowed to run. They called for a boycott of the elections.

In their absence, a stranger was carried by the people. However, the elected candidate, Dr. Basile Adjou Moumouni, gave the military grist to grind. An international civil servant of the World Health Organization based in Brazzaville, the elected head of state was not a member of the political seraglio and did not reassure the military. They certainly had concerns about the maintenance of their privileges.

In doing so, the military used the low turnout as an excuse to annul the result of the elections. In the aftermath, in the face of pressure, on July 17, 1968, they installed a replacement civilian in the Presidency: Émile Derlin Zinsou.

The new head of state, a former member of the Assembly of the French Union, was in fact the country’s fourth leading politician. Accustomed to Dahomean political life, he was the consensus within the Military Revolutionary Committee (CMR).

With the old demons still inhabiting the Army, it was once again in the spotlight. Colonel Maurice Kouandet ousted Emile Zinsou from power on December 12, 1969. As usual, he did not lead the country. He entrusted the management to another officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Emile de Souza. In May 1970, the military pledged to step down as head of the Executive. To ward off the fate of instability, a new formula was found: a rotating presidency was introduced. It consisted of the formation of a government led in turn by the three main civilian political actors: Maga, Apithy and Ahomadégbé.

The country’s three political leaders, who are firmly anchored electorally in a region, are expected to succeed each other in the supreme magistracy every two years. At the end of Hubert Maga’s term in May 1972, Justin Ahomadégbé took over. But the formula didn’t catch on for long. On October 26, 1972, the Army seized power again, with Battalion Chief Mathieu Kérékou. He swept away this triumvirate, derided as a “three-headed monster.” This was the beginning of the country’s second political highlight.

The second phase, military-Marxist, extends from this seizure of power at the National Conference of February 1990. In 1975, the military government made decisive strategic and ideological choices. The Republic of Dahomey is renamed the People’s Republic of Benin. It proclaimed its adherence to socialist economics with a Marxist-Leninist orientation. The country was draped in a dictatorial cloak of the country. Several opponents were murdered, tortured and exiled. From the mid-1980s onwards, the government was cornered by an unprecedented economic situation, which was the result of a series of factors: international gloom, mismanagement, concussion, and incompetence.

In bankruptcy, the state stopped paying salaries. Faced with this situation, fed by the ideologues of the Communist Party of Dahomey, the streets were rumbled with protest demonstrations. Disarmed, the military-Marxist junta resigned itself to political, economic, and social reforms. On December 6, 1989, it abandoned socialism as the ideological orientation of the state and convened a National Conference. In addition, political prisoners were granted amnesty and were allowed to return to participate in the “Estates-General” announced for the month of February.

The time of Democratic Renewal, consecrated by this great mass of the living forces of the Nation, is still in progress. From 19 to 28 February 1990, the National Conference brought together more than half a thousand delegates from the different components of the country at the PLM Alédjo Hotel under the chairmanship of Monsignor Isidore de Souza.

Two main decisions came out of it. The first established economic and political liberalism, democracy and the rule of law. The second appointed a prime minister to assist General Mathieu Kérékou, who remained president but was stripped of most of his prerogatives. A wind of democratic renewal swept through Benin.

The Prime Minister appointed by the National Conference, Nicéphore Soglo, Executive Director of the World Bank, is responsible for leading the government through the transitional period. The task of this government is to implement the main measures leading to the adoption of a new Constitution and the organization of general elections. Unlike the other transitional experiences of the countries of the sub-region, the two main actors of this period, President Mathieu Kérékou and Prime Minister Nicéphore Soglo, were able to play their part loyally and tune their violins during the twelve months of its duration.

On 11 December 1990, a new fundamental law, that of the Fifth Republic, was promulgated after its adoption by referendum. It reflects the decisions of the National Conference. It is based on democracy and the rule of law. It opted for a republican presidential system with a separation of the three powers: the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary.

Three months later, legislative and presidential elections marked the end of the transition period. The new unicameral National Assembly is elected for a four-year term. It is chaired by Adrien Houngbédji, a lawyer and former political exile.

In the second round of the presidential elections, Nicéphore Soglo triumphed over Mathieu Kérékou. But in 1996, he had to give up his presidential chair to Mathieu Kérékou after the presidential elections. Five years later, the people of Benin once again put their trust in General Mathieu Kérékou.

In 2006, in the absence of Mathieu Kérékou and Nicéphore Soglo, the political game became more open. The first round of elections was held on 5 March 2006. Twenty-six candidates were vying for the highest office: regulars and newcomers. Among them are Adrien Houngbédji and Bruno Amoussou, both former ministers of Kérékou and former presidents of the National Assembly. Against all odds, it was Boni Yayi, portrayed by his opponents as the emanation of “a spontaneous generation in politics”, who stole the spotlight from them. He won the final decision with more than 75% of the votes cast. The following year, his supporters, united in the Cowrie Forces for an Emerging Benin (FCBE), won the legislative elections. In the aftermath, the elected president of the National Assembly, Mathurin Nago, came from this movement.

Two main players emerged within the Beninese political class: the President of the Republic Boni Yayi and his challenger in the second round, Adrien Houngbédji, who acted as the “main opponent” of the government.

In 2011, Boni Yayi was re-elected for a new five-year term as President of the Republic in the first round of the presidential elections.

In March 2016, the Beninese people elected Patrice Talon after the second round of the presidential election. On April 6, 2016, Talon was sworn in and he took over the reins of power.

Reference: gouv.bj/pages/histoire/