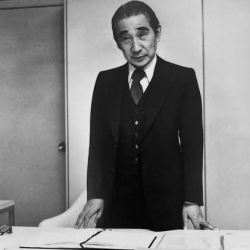

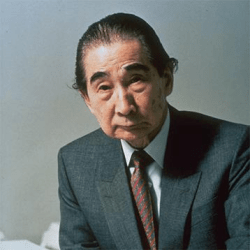

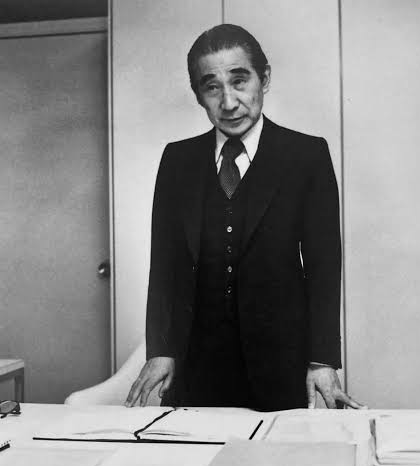

Kenzo Tange (1913–2005) was a pioneering Japanese architect and urban planner whose work reshaped modern architecture in Japan and around the world. With a career spanning over five decades, Tange’s designs harmonized traditional Japanese aesthetics with the sleek, functional forms of modernism. His groundbreaking architectural projects and innovative urban planning concepts earned him international recognition, including the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1987.

Tange’s architectural philosophy, which emphasized the integration of modern technology and design with cultural and historical sensitivity, marked him as a visionary. He was a central figure in the post-war reconstruction of Japan, where his projects became symbols of the nation’s recovery and modernization.

Early Life and Education

Kenzo Tange was born on September 4, 1913, in Osaka, Japan. He spent his early years moving between different cities due to his father’s job as a civil engineer, which exposed him to various aspects of the built environment. His interest in architecture began after seeing Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier’s plans for the Soviet Union’s Palace of the Soviets. This sparked his desire to pursue architecture as a career.

Tange studied architecture at the University of Tokyo under the guidance of prominent Japanese architect Hideto Kishida. He graduated in 1938 and later became a professor at the university, where he would mentor many future architects. His education during this time was influenced by a mixture of traditional Japanese building techniques and modern Western architectural theories, which shaped his unique design approach.

Architectural Philosophy

Kenzo Tange’s architectural philosophy was rooted in the belief that architecture must evolve in response to the cultural, historical, and technological context of its time. He sought to combine the modernist ideals of functionalism and simplicity with elements of traditional Japanese architecture, such as spatial fluidity and the use of natural materials. Tange believed that buildings should not only be aesthetically pleasing but also serve as functional spaces that reflect the societal needs of the time.

One of the hallmarks of his work was the way he incorporated megastructures—large-scale buildings or urban designs that could accommodate future growth and changes—into his projects. This philosophy became particularly evident in his urban planning proposals, where he envisioned cities as organic, adaptable systems.

Early Architectural Works

Tange’s early career was marked by his participation in competitions and small-scale projects that gained him recognition. His first major breakthrough came in 1942, when he designed a memorial to commemorate the first anniversary of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. However, World War II interrupted the project, and it wasn’t until after the war that Tange’s career truly began to take off.

His work after the war reflected the necessity for rebuilding Japan, and his early designs were often characterized by a combination of modernism and functionality, aimed at helping the country recover from its wartime devastation.

Post-War Architecture and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial

One of Kenzo Tange’s most iconic early works is the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, completed in 1954. The park, located in Hiroshima, was designed to commemorate the victims of the atomic bomb and promote peace. At the center of the park stands the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which showcases Tange’s ability to blend modernist architecture with symbolism and emotion.

The park’s layout and the design of the museum reflect the tragedy of the atomic bombing while offering hope for a peaceful future. The use of concrete, a modern material, juxtaposed against the open, contemplative spaces, created a profound and solemn atmosphere. This project catapulted Tange into the international spotlight, marking him as an architect capable of using architecture for cultural healing and national identity.

The Tokyo Plan and the Metabolism Movement

In the 1960s, Tange became a central figure in the Metabolism movement, a group of Japanese architects and designers who advocated for the use of organic, flexible structures that could grow and change with time. One of his most famous contributions during this period was the Tokyo Bay Plan (1960), an ambitious proposal to reorganize Tokyo’s urban landscape by creating floating cities and interconnected megastructures.

The Tokyo Plan envisioned a city that could expand outward into the bay, using modular, adaptable units that would allow for the rapid urbanization and population growth that Japan was experiencing. While the plan was never fully realized, it had a profound influence on urban design and the concept of adaptable architecture.

Major Architectural Projects

Kenzo Tange is perhaps best known for his groundbreaking designs in both architecture and urban planning. Some of his most famous projects include:

- Yoyogi National Gymnasium (1964): Designed for the Tokyo Olympic Games, the Yoyogi Gymnasium is celebrated for its sweeping, suspended roof design, which blends traditional Japanese forms with modern engineering techniques. The structure is an architectural masterpiece, with its flowing lines and dramatic tension cables.

- St. Mary’s Cathedral, Tokyo (1964): A striking example of modernist religious architecture, St. Mary’s Cathedral features a cruciform shape with bold, sweeping curves. The building’s minimalist design and use of concrete give it a spiritual and monumental quality.

- Osaka Expo ’70: Tange was the master planner for the 1970 World Expo in Osaka, where he showcased his vision for the future of urban environments. His designs for the pavilions and the overall layout of the expo site were innovative and reflected his ongoing exploration of megastructures.

International Projects

Kenzo Tange’s influence extended beyond Japan, as he worked on numerous international projects. His work included:

- The Italian Embassy in Tokyo (1964)

- Master Plan for Skopje, Macedonia (1965): After an earthquake devastated the city, Tange was invited to help design a new master plan for its reconstruction.

- The United States Embassy in Tokyo (1967)

He also worked on projects in Nigeria, Kuwait, and Singapore, bringing his distinctive blend of modernism and cultural sensitivity to diverse global contexts.

Urban Planning Contributions

Tange’s contributions to urban planning are as significant as his architectural works. His vision of cities as flexible, organic entities capable of growth and change was ahead of its time. His ideas in the Tokyo Bay Plan and his work on cities like Skopje influenced urban planners worldwide, promoting the idea that cities should be adaptable to future needs rather than static structures.

Kenzo Tange’s Influence on Global Architecture

Globally, Tange’s designs and urban planning concepts have influenced the work of countless architects. His ideas about integrating culture and history into modern designs resonated with architects looking for ways to create meaningful spaces in the rapidly urbanizing world of the 20th century.

Awards and Recognition

Throughout his career, Kenzo Tange received numerous awards, including the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1987, often regarded as the highest honor in architecture. He was also awarded the Order of Culture in Japan and numerous other international accolades.

Kenzo Tange Associates

Kenzo Tange founded Kenzo Tange Associates, an architectural firm that continues his legacy today. The firm has worked on many significant projects worldwide, ensuring that Tange’s design principles live on in contemporary architecture.

Challenges and Controversies in Tange’s Career

While Tange’s work was generally well-received, some of his ambitious urban planning projects, such as the Tokyo Bay Plan, were criticized for being overly utopian and impractical. These projects, though visionary, were often deemed too large-scale to be realistically implemented.

Personal Life and Legacy

Kenzo Tange was a deeply philosophical man, often reflecting on the role of architecture in shaping society. He passed away in 2005 at the age of 91, but his influence on architecture remains strong. Today, he is remembered not just for his buildings, but for his profound impact on urban planning and modernist design.