Obollo people are largely farmers, some are business men/women and civil servants.

All the various Obollo communities are seen as genealogically, historically and culturally related; and this is not doubtful as there were some ceremonies — social/traditional functions (prominent among which is Olenyi Obollo festival hosted every December 27) which require the collective activities of all towns together. These ceremonies are orthodoxical. And every Obollo descendant look forward to them.

The ancestral relationship that binds Obollo communities is so thick that one may not be wrong if one describes them as a tree and branches, planted and watered by only one hand.

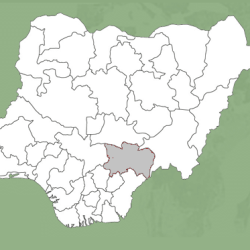

Olenyi is the tree and Obollo Afor, Obollo-Orie, Obollo-Etiti, Obollo-Nkwo, Obollo-Eke, were all its branches, with numerous subsets.

Obollo people do not trace their origin to Israel, Egypt, Ethiopia or any distant place like many Africans do.

Popular oral account of the people stated that Nnam Edu Enyi who hailed from East-Abakaliki had three male children who were Olenyi, Otase Enyi and Igwuru Enyi.

Olenyi was the father of Obollo; Otase Enyi fathered Asokwa who also fathered Ikem (hence the name Ikem Asokwa), while Igwuru Enyi fathered Eha Amufu.

When Olenyi grew up he married four wives three of whom bore one male child each for him amounting to three sons. These three sons were Ugbabe Olenyi, who was the eldest; Ezejo Olenyi the second son, and Ekpa Olenyi the third. He would later have another son called Ohullor who was born pre-maritally by one of his daughters. The name “Ohullor” which could transliterationally mean “begotten at the backyard” was onomatopeic to denote that he was born without the mother being married. He was accepted as a legitmate son.

The four sons who later grew up preferred to settle at the four regional ends of the land i.e. north, east, west and south bearing the suffix of the distinct four Igbo market days in their block names. Thus they formed the triad quartet, as it were, of Obollo Afor, Obollo Eke and old Obollo Etiti (which housed the now autonomous Obollo Nkwo and Obollo Orie communities).

The great grand Patriarch, Pa Olenyi was also said to be cosmopolitan. He made his house a home for all. He was a famous hunter. And most of his contemporaries had strong affinity for his ingenuity in the art. So from far and near he was courted; and his family members acquiesced to friends from neighbouring towns. This was how he begot another amiable son – Iheakpu Obollo.

Iheakpu was believed to have naturalized into Pa Olenyi nuclear family, supposedly from Iheakpu Awka, in present day Igbo Eze south LGA. And today, the family ties of Olenyi sons and Iheakpu Obollo is inseparable, and transcends mere inter-family adoption.

There was a remarkable story that is supposed to breed feud, chaos, and division among the four sons of Pa Olenyi. But it never did. Generations have come and gone observing the norms created by this story without qualms. And that might point to the veracity of the said narrative.

The story can be tagged: Ugbabe demotional theory. It states that of the four sons of Olenyi, Ugbabe was the first and the most exposed (and by modern terms, most civilised). He was brilliant and parades pronounced self-esteem, and therefore, proverbially distanced himself from jobs (e.g farm practices) that dirties or stains his always-clean garments. He was said to be always neat hygienically.

On a fateful morning, he was told by his father Olenyi to fetch palm oil and other slimmy amulets for libations to “okike egų” (the earth goddess of soil fertility). This was an annual pre-planting season ritual that would later metamorphose into the present day “Ejo okike” festival in Obollo tradition. But he was said to have ‘arrogantly’ refused to obey his father for obvious reason that the oil will stain his clean garment.

Olenyi, (now enraged), calmly controlled his burning rage and asked his younger ones to help out, and they readily did. This irked him the more, and he raised a verdict (curse) out of anger, that Ugbabe can never superintend over his family even if he became the only surviving son. Pa Olenyi pointedly declared that Ugbabe can never be crowned the “Onyishi” Obollo (the eldest who attends to ancestral deities). He can never wield the family “ofo” symbol.

What was not clear is if the verdict was meant to be trans-generational or it was meant to be served out by patriarch Ugbabe alone.

But that should be topic for another day!

However, from that day till this moment, no Ugbabe descendant has ever been crowned “Esha” – Onyishi Obollo, despite being the most populous, educated and prosperous branch of the Pa Olenyi family tree.

History therefore records that the people of Obollo are the direct descendants of the four sons of Olenyi, who in turn was the first son of Nnam Edu Enyi.

The family tree here exemplifies the close relationship of Obollo with Ikem and Eha Amufu but owing to frequent strife arising from land disputes, that closeness only exists in mere genealogical nomenclature as seen today.

Recently there have been series of re-unification attempts aimed at restoring the closeness that the various people of Obollo, Ikem and Eha Amufu once esteemed but it has not really seen the light of the day; perhaps due to the approach or unwillingness of the people to revisit their history. But it is hoped that the mutual and warm intimacy that once existed among them be rediscovered soonest.

MIGRATION THEORY

Ulon’Obollo is believed to be the place where Obollo migrants first settled. It was from this point that they spread to the other places that they can be found today. Also at a time in history there was a scramble for the occupation of lands leading to migrations to uninhabited lands from the original place of settlement.

Ezejo moved to Ada and Umuitodo. By that time, he was holding the patrichal mantra as the head of Olenyi descendants (following the Ugbabe’s demotional theory narrated above). So he called the shot. When he realized that the unoccupied lands of Umuitodo was more suitable for him than the land he previously settled he swiftly decided that he and his family members settle on whichever land he considered more arable.

Later in history, the present Obollo-Eke land opened up and an unchecked whirl of desire to acquire spaces in that land became so severe that there was organized fighting by young men to settle there. This mad rush to settle in Obollo-Eke also led to near abandonment of Obollo-Afor as everyone scampered for a space to settle in that southern part of Obollo land. Within a short while, Ikem and Leke people were driven from Obollo-Eke and replaced by Obollo-Afor settlers. Today, the Ikem and Leke are found in present day Isi-Uzo while Obollo is in Udenu.

In recent times, other Obollo communities have developed elaborately, as a result of series of inter-lapping migrations from the original place of settlement; coupled with creation of more development centres and autonomous communities by the state government for political and administrative convenience.

What we today know as Obollo Etiti was a confluence of Umu Ugbabe and Umu Ohullor descendants who occupied the uninhabited low land between Obollo Afor and Obollo Eke. Population explosion would lead to the disintegration of the whole into two more autonomous communities along patriarchal family ties — Obollo Orie (predominantly inhabited by Umuosigide) and Obollo Nkwo (mainly Umuitodo, Umuoleyi, Umuosogwu Umuokoriko, Umuonyeke and Ndaburu Afube).

Iheakpu descendants today inhabited the Northwest poles of Obollo, in the Afor axis. And they were famed as successful merchants of Obollo land. Their business prowess is enviable. Thus, they contributed a lot in the development of Obollo Afor market. They were habitual traders.

Umuosigide

Umuosigide that constituted the greater part of Obollo Orie are direct sons and daughters of Osigide, a son of Ugbabe. Osigide Ugbabe was a great hunter and warrior. A giant that was said to have wrestled an Ape of Chimpanzee specie, which snatched Ugbabe’s ritual drum from their shrine.

He pursued the animal with bare hands and strangled it and took the drum. Osigide whose children now occupy the vast lands of Umuosigide Ulo and Nkalagu Umuosigide (sharing boarders with Ada, Ogbodu Aba, Ezimo and Obollo Afor), was famous for his wrestling intrepidity in those prehistoric times when traditional wrestling contest was a major recreational activities of the post-planting season. His aura mimicked Okonkwo the hero in Prof. Chinua Achebe’s book — Things Fall Apart. And that’s how the ballad nugget: “Osigide Ugbabe Ijike nar’ Adaka abia” became both community and individual attributes of every son of this great warrior.

Ada

Obollo Etiti is dominated by children of another Ugbabe’s son called Ada. He was believed to be the immediate elder brother of Itodo Ekpo Ugbabe, and a half brother to Osigide. It is said that his own Mother came from Idoma land of Benue state.

Inter-tribal marriage helps a lot in modifying and improving native civilization. Obollo people as noted ealier, taking after their progenitor, Pa Olenyi were cosmopolitan. They don’t discriminate against people of diverse world view. They marry and gave in marriage to neighbouring communities. And in the midst of strong marital love affection, after giving birth to many children, the couple may decide to name at least one of their kids after the wife’s native names.

This must have informed some names that are shared with Idoma people in Obollo. Names like Ádá, Idoko, Agbo, Onuh, Abah etc were common in both Obollo and Idoma lands. And so it was difficult telling which of the two holds patent over which name.

But in the case of Ada, considering that in Igbo cosmology, Ádà is feminine name for “daughter,” it is believed that Ádá of Obollo Etiti was the son of Ugbabe who was named after his maternal culture of Idoma (Ugbabe’s in-laws). This is supported by the fact that Ádá is masculine in Idoma language denoting “Father.” The difference is in the emphatic stress and intonation marks.

All the Ugbabe sons, including Ada, Itodo, Osigide, etc were famed for their industry and exposure.

A central deity that protects all Ada sons and daughters predated Ada history. The deity was called Abatiji. It was a fearsome Oracle that was said to come out every Orie day in the guise of thickly maned Lion. All “akpaka” — ukpaka (Oil bean tree) in Ada were dedicated to it. And that was why till the last three decades when Christianity took grip of most of our people’s loyalty, Ada people don’t use Mgbawa Akpaka (Pods of oil bean fruits) to make fire. The deity has its shrine at the base of a mighty Iroko tree situated at Orie Ada market place. It was believed that from the height of that Iroko tree, Abatiji heralds protection to all Ada indigenes wherever they may be.

But when Elder Christopher Ugwueze (Alias Echakala), a christian apologist, and a controversial Catholic, became the Onyishi Ada, he told “Oha Ada” (Ada elders council) that the tree is too old and should be felled. Vehement resistance arose from some of the worshippers of the deity. But since our custom gave absolute power to Onyishi in deciding such matter, they left it to his prerogative. And he fearlessly cut it down, and lumbered it.

Few years after, the ancient Ukwu Akpu Obollo Afor that was also said to house a revered spirits was hauled down by slight wind, causing collateral damage to lives and property estimated in millions. This was an indication that it has aged so long that it could not stand the whirl of slight wind.

Prior to that, the Akpu Ukwu Igbudu which housed the popular Ukwu idenyi Amoda spirits at Amegu Ada was blown off by wind at night. About the same period, another historic Akpu tree at Ugwu Mkpufu (Umuochi) suffered similar fate. All within twelve calendar months.

And so people began to see reasons with Elder Echakala. He was right in demanding that Abatiji’s ancient Iroko tree be felled to avert potential danger which it poses to lives and property.

But the worshippers of the shrine saw it as a fight between Christians and pagans.

To these trees were attached some fetish powers as they were dedicated to the worship of certain gods; thus they were in the belief of traditional worshipers untouchable. Till date, Ezza and Okpuje Ada respectively still have two mighty ancient Iroko trees in their village squares that are dedicated to the worship of their village deities, which guards them.

Umuitodo

Itodo Ekpo’s sons settled very close to Ada their father’s elder brother. They share mutual boundary to the west with Ada, and to the East with Idoma land. He too had his sons migrate southward to have fair share of the Obollo Eke renaissance after Leke and Ikem were driven away. It was one of his sons who participated in the struggles that settled in Ibenda – alternatively called Umuitodo Egų. The entire descendants of Itodo (especially the African Traditional Religion’s adherents) keep annual feast of their ancestral deity called “Chukwu. abiama.” At the threshold of that deity is a central market dedicated to it, which comes alive every Nkwo market day – Nkwo Chukwu

Umuitodo Ulo

Umuitodo Ulo and Umuitodo Egų are bilaterally analogous to Umuosigide Ulo and Nkalagu Umuosigide respectively. Same as Ada Agu and Ada Ulo, Umuezejor Obollo Eke and Umuezejor Obollo Afor. Iheakpu Obollo Eke and Iheakpu Obollo Afor. Ogwu Obollo Eke and Ogwu Obollo Afor etc. It was the souvenir of cross-migration in the ancient days that survived till date.

It was said that the invasion of marauding hunters from Idoma into the forests of Ibenda called “Ekwu mkpo” in the stone ages made Ibenda and his sons mount checks and battle against them. They defeated and pursued them off their territory.

Ibenda is also famed for high moral probity. It was said that any of their sons who committed theft or brigandry of any sort will meet stern warning from the “Oha Ibenda” (Ibenda elders council), and if he continues in the way of infamy they would summarily sniff him out. A thick dreaded ‘evil’ forest – “Ekwu mkpo” was a point-of-no-return for deviants who violated social order in those days. And while such jungle justice practice is no more obtainable in modern times, the story still resonated; and affords great respect to them as people with zero tolerance for social misfits.

Ekwu Mkpo can today fit into a native game reserve. Sometime last year, there arose dispassionate advocacy in some quarters, that Ógó Ugwu Ezugwu Amalla, and Ekwu mkpo be harnessed to become great sites for tourism. Ibenda has maintained her own thick forest till date. They can be repositioned to attract tourists, as game reserves.

Ohullor

In all these, it is only Ohullor that is found in all the three old Obollo trunk. There is Ohullor in Obollo Eke, Afor and Etiti.

Obollo hospitality nature

Affinity for neighbours and kindreds alike is evident in the community of mixed dwellers of Okparigbo Obollo Eke after the battle between Ikem and Obollo.

During the 1930 Obollo-Ikem inter-community war, some warriors from neighbouring clans fought on the side of Obollo. At the end of the battle, fearing that Ikem with their Odo deity might still fight back, Obollo as the victor, allowed some.of the warriors to occupy the land, since vacuum is dangerous at that instance. This made Okparigbo the cosmopolitan centre of Obollo town, in that today it hosts people from every other families in Obollo.

Similarly, Umuoleyi still host a large population of Imilike migrants and settlers in their midst and they had lived harmoniously for years. The cohabitation dates back to antiquity when the founders of Oleyi kindred sought the help of their friends from Imilike during the struggle for land acquisition. They helped Oleyi conquer in the struggle and they have shared the spoil mutually ever since.

Similar story goes to Umundu dwellers in Ada Obollo Etiti. The progenitors of Umu Agboeje kindred of Ada welcomed the Igboke patriarch from Umundu and offered him a large scale of land for free as a friend. They lived together savouring the milk of friendship till death. Their descendants had continued the harmony to this day, such that it will be hard for them to go back to Umundu permanently again.

Obollo ancestral capital

Obollo-Afor traditionally remains the mother home of the Obollo people within which every single Obollo indigene is thought to have ancestral link. It is therefore not surprising that the town accommodates Obollo indigenes from Obollo-Afor, Obollo-Eke, Obollo-Etiti Obollo Orie and Obollo-Nkwo.

As the “capital” of Obollo clan. It is a metropolitan zone that has undeniably grown to an urban town from a little known settlement.

In general, the roll call of the communities/villages that today constitute Greater Obollo Clan are as enumerated below, and we intend to discuss more on each of them in subsequent volumes of this piece:

Obollo Afor that comprises:

Ulon’Ubollo, Umuezejor, Ogwu, Amutenyi, Ohullor, Iheakpu.

Obollo Orie

Umuosigide, Umuosogwu, Umuoleyi, Umuonyeke, Ogba, Okpufu, Nsama.

Obollo Nkwo:

Umuitodo, Okpakerekere, Umuokoriko, Ndaburu Afube.

Ibenda (Umuitodo Eg’) an offshoot of Itodo Ekpo, is already an autonomous community too. It houses villages like: Ajama, Mkporogwu, Echara, Ngele-Okpo, Idoko. Uburu, Umuero.

Obollo Etiti has:

Ada (Amagu, Amoda, Akparata, Okpaga, Odenigbo, Ezza, Uzo Agu, Akanugu, Egudele, Agamede, Mkpunator, Odobido). Umu Enibi, Ohullor Etiti, Umueyioda, Ugwu Eke.

Obollo Eke has:

Amutenyi, Isielu, Ogwu, Agala, Mgbugbo, Ugbabe Uwal’, Ejuona, Iheakpu, Ohullor, Umuokpe, and Okparigbo.

RELIGION

The people of Obollo practiced African Traditional religion (ATR) which was the dominant religion in the precolonial Africa, but with the advent of Christianity, a good percentage of them converted to the new religion. This was enhanced by their large heartededness that makes them embrace foreigners with both arms in trust.

Traditional religious feasts span through five Luna seasons in every native calendar year. They are Onwa Esaa, Onwa eno, Isi Ji, Ejo Okike and Omabe (the only triennial feast in Obollo).

The ATR adherents in Obollo, have pro-life approach to morality, hinged on the golden rule: “Do unto others as you would them do unto you.”

In the native religion, they consult the spirit world through shrines, oracles, and ancestral deities ministered to, by human agents (priests and priestesses).

Masked spirits (masquerades) play important roles in the celebration of certain seasons of each religious festivity. They also act as intermediary between the people and the spirit world.

In adorning the masks (especially Akatakpa), the operators hang a double-stringed sash tied to a horn or ofo stick. This is called “Okaran’abo”. It is a customary symbol of justice and fairness. And as the man wears the mask, he will hang the sash across the humerus (shoulder) region uttering the following incantative words “ekorum onye ozo ekole m, mèè nke m ekole onye ozo.” (May my displays and outing cause no harm to anyone, and may no one’s malice have effect on me).

And until this new era of rampart gross religious profanation, this practice persisted as a guarantee that our masquerades were majorly for entertainment, education, and security in both social and ATR spheres.

But when early European missionaries arrived through Uzo Uwani, about 120 years ago, our people embraced Christianity massively. They gifted their landed property to the missions and some of their sons and daughters to the seminaries and convents.

Thus the dominant religion of Obollo community today is Christianity and the people are mainly Catholics. It is therefore not surprising that many of the illustrious sons and daughters of Obollo are Reverend Fathers and Sisters. There are not less than six parishes housing more than half score outstation catholic churches in Obollo-Afor alone so that nearly all the communities that make up the town has at least one parish.

Old Obollo-Etiti has three parishes (one each for Ada, Obollo Nkwo and Orie) with many outstations scattered around the town. Nkalagu Umuosigide is already at an advance plan of having their dream of parish actualized. Umuoleyi is on the que as well.

Obollo Eke town has Ibenda parish carved off it, with Ogwu soon to follow suit.

Catholic as the predominant faith of the people testifies to various Catholic mission schools that dotted our landscape before government took them over from the missionaries. They brought education and integral western civilization to Obollo, as they did many other Igbo zones.

It therefore makes it impossible for the history of the people to be written without recourse to missionary activities of the catholic church.

Anglican Church was the second most dominant church in Obollo, having not less than four parishes producing about 10 indigenous priests, and many Catechists. They also built schools under the Church missionary society (CMS). Rev. Canon David Ogbonna (Late) was soaring higher in his vocation as the pioneer indigenous Anglican priest of Obollo when death struck and snatched him away. He had risen to the rank of Archdeacon before his demise.

However, over the last three decades, other Christian denominations — Deeper Life Bible Church, Redeemed Christian Church of God, Living Faith Church, The Lord’s Chosen Charismatic Ministries, Christ Embassy, Watchman Catholic Charismatic church etc have found their bases in Obollo too.

NAMIMG CEREMONY

Obollo people cherish birth and new born babies so warmly. They discourage and detest abortion under any guise. At birth even long standing enemies break the feud to celebrate the birth of the new born in the enemy’s family.

Tubers of Yams are donated freely to the parents of the child and often kept close to the bedstead for the nourishment of the nursing mother. This is called “Ji isi ogodo” (Tubers for postnatal care).

The ritual of Naming ceremony in Obollo land is also unique and conveys a lot of socio-cultural meanings.

On the 8th day after birth, the nuclear and extended family members of the new born gather usually at the dusking hours of the day to perform the ritual. It was under the evening sunset that they perform it. This is significant as it points to the baby that s/he will live long till the evening of longevity.

The father carries the child and after pronouncing some words of wisdom nuggets, prayerfully wish him/her longevity and uprightness above the lust for wealth.

At this point, the father (still carrying the baby) flanked by the wife calls the child a name they had agreed prior to that day. This scene cuts the image of Zechariah (LK.1:59-64) in the naming of John the Baptist. All will clap and then after that, the father will take some time off to justify the choice of the name they gave the child.

The eldest man of the kindred or his representative will carry him/her and use the leaf of a non-bitter specie of venonia amygdalina (Bitter leaf) called Awó in our dialect to touch the child’s lips. Awó serves as a sacramental in the rite of naming ceremony denoting outspokeness. This symbolizes the wishful prayers that the child must be able to defend him/self coherently in all his/her dealings in life, whenever and wherever the need arises.

Then he will paste a little morsel of pounded yam (which signify perpetuity and permanence of family hegemony till the geriatrics of days) on the child’s palm. He will pray for his/her longivity and good health. Each member of the family and well-wishers present will take their turn to do same.

However, with modernity affecting almost all aspect of our culture, this ceremony at some quarters of Obollo have been finetuned in line with borrowed norms and christian tenets. But this pattern described above still finds its relevance in whichever method they adopt.

Music, wining and dining, and plenty of merry-making accompany the ceremony at a highly pronounced stage, in accordance with the economic status of the child’s parents.