Communities: Anokyi, Ahonlenzo, Baku, Ellembelle District

Language: Nzema

Region: Western Region of Ghana

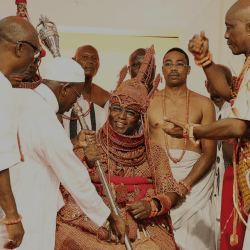

The main cultural festival of the Nzema and Ahanta people of South Western Ghana is the Kundum Festival. It is celebrated every year in September and October. Contrary to public opinion that today takes Kundum as a kind of “harvest festival,” it is and was a social and religious festival that played an important role in community sustenance and cultural cohesion but has been losing much of its deeper meaning through socio-historical changes in the 20th century world, a problem not restricted to intangible heritage and communities in West Africa.

It has been waning as a cultural practice over the last decades and must be seen a highly endangered part of Ghana’s Living Heritage. Kundum is the traditional festival of ancestral veneration and prosperity in life and builds on intangible cultural practices like music, dance, drama, and oral narratives. Recent years and social changes have made it more and more difficult for the Nzema to preserve and “manage” this cultural tradition and heritage.

The duration of the festival has been reduced over the years from several weeks to one week and it has partly been transformed into a “way to bring the community together and remind the Nzema and Ahanta people of their traditional cultural values,“ as one observer rightly said, which albeit implies a loss of the deeper social and cultural significance and potential of Kundum.

Kundum founding narratives, oral history, musical heritage and social functions Nzema culture and heritage centres around the mythological and cosmological content inscribed in the Kundum celebration as well as narratives and songs of the origin of culture and music which are tightly interwoven with communal understanding, cohesion and identity.

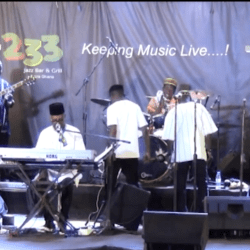

Like in other West African traditional festivities, Kundum includes a ban of musical activities and forms of social merriment from public life and thus creates one week of silence and solitude, which is in the 2nd week of September and marks the beginning of the festival.

The purpose of this silence is the veneration of the ancestors, which plays an important part in Nzema cosmology. For one week, all musical instruments are deposited at the local cemetery, the resting place of communal ancestors, and community chiefs/leaders and elders pay their respect to their ancestors by visiting the cemetery.

According to oral history, “invisible teachers” known in the Nzema language as “motia” (translated as “dwarfs”, so perhaps “first humans” like Xoisan) return for two days every year during the last week in September to the land where they once taught a captured hunter the rhythms of Kundum.

Although they are invisible they make the Nzema aware of their history as the subtle and at the same time highly propulsive musical rhythms of Kundum are heard across the area.

The Story of MOTIA as recorded from Oral History (source Anokyi/Akablay family) “A hunter went to the forest in the night to hunt and got lost. For almost four months the search group combed the whole forest and could not find him. In the fifth month he resurfaced and told his story. He was taken away by some motia to their world, and while he was there, they fed him every morning and evening with the kind of food they eat, and every evening they gathered at the centre of the place, beat their drums and chant their songs and dance in a circle for two and half hours before they retired to bed.

Anytime this happens the hunter asked them what they were doing but they won’t mind him, but on his last day at their place, he asked again and they told him that the dance they dance every night is called ABISA, meaning “you have asked,” and the celebration is called KUNDUM, because it is the beginning of good fortune.

After this the dwarfs took the hunter back to his town and told him to tell the people that every 2nd week of the 9th month of the year the whole community should gather at the centre of town, and that they would also come there to beat the drums, so that he would be able to teach his people the dance and the songs, that they taught him.

And truly the motia going by their word came to town beating the drums but nobody saw them they only heard the sounds of the drums and they started dancing to the rhythms amid chanting and singing. This went on for four years and then they stopped coming because the Nzema people had already learnt everything.” The custodians of this musical knowledge, art and heritage of “morally good life” became the EKPUNLIBAKA (or Ekpunli Baka).

According to oral history: when the hunter was brought home by the invisible motia, he told the town what he had experienced and learned. The Ekpunli Baka were the first ones who learned the songs he brought from them and they are the chanters when Kundum drumming and dancing goes on. Today the Ekpunli Baka are a social traditional singing group of 7-9 people who preserve the Nzema songs.

They are still the chanters in the festival when drumming and dancing goes on, and thus keep musical heritage alive. At the same time, and this points to the nexus of moral and ethical thought and music heritage in Nzema Intangible Cultural Heritage, play an important social role as moral authority and disciplinarians in their community and as important agent of communal cohesion and moral well-being.

During the year, their role is to observe and gather information about the doings of the leaders of the community, the chief and elders, and during Kundum time, they are making this public. If you “performed” well, then they will chant your good deeds for you, if you didn’t they will voice that too.

The community leaders are supposed to take this in good faith, and to reward them for their moral judgements, that serve the betterment and sustenance of humanity in Nzema. Otherwise as the story goes, they would not live to see the next Kundum festival because that’s what the gods use to expose bad doings in the community. Kundum annually strives to re-enact “the beginning of good fortune.”

The Kundum Festival is still practiced in the Western Region but has lost significant parts of its social and cultural meaning and content as much of its foundational music, dance, and story repertoires have been dwindling substantially, are widely forgotten, only preserved in the minds of a few experts. They are highly endangered Living Heritage of Ghana today. Unless they are revitalized and sustained in the near future, this immensely important part of Ghana’s Intangible Cultural Heritage will be lost.