Afghanistan presents a paradox of immense resource potential and chronic underdevelopment. Despite recurring headlines about its “$1-trillion in mineral wealth,” in practice the country remains among the poorest in the world. Its economic performance is constrained by geography, conflict, institutional weakness, and external isolation. Yet, even under difficult conditions, incremental signs of stabilization are emerging as of 2025. This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date overview of Afghanistan’s macroeconomy, structural constraints, sectoral dynamics, and outlook.

I. Macroeconomic Overview & Trends

1. GDP and Growth

- As of 2020, Afghanistan’s nominal GDP was estimated at about US$20.1 billion, while its PPP-adjusted GDP was about US$81 billion.

- More recently, official and market-based sources suggest the nominal GDP has declined. According to World Bank / TradingEconomics data, in 2023 the GDP was about US$17.15 billion.

- Some forecasts expect nominal GDP in 2025 to reach US$17.49 billion, reflecting modest recovery.

- In PPP terms, some sources (e.g. World Economics) estimate 2025 output at US$183 billion, though that figure appears optimistic relative to other projections.

- Growth has been weak but positive: in 2024, GDP growth was approximately 2.5 percent, and 2025 is projected to show 2.2 percent growth amid headwinds.

- The Asian Development Bank expects about 2.6 percent growth in 2025 and 2.2 percent in 2026.

- Real growth is severely constrained by structural challenges, limited investment, and volatile aid flows.

2. GDP per Capita

- In PPP terms, the per capita GDP has hovered at around US $2,459 in earlier years (e.g. for 2020), though more recent data show lower figures consistent with economic contraction.

- Nominal per capita GDP is far lower (e.g. US $600+ regionally).

- According to the World Bank, the PPP per capita series for Afghanistan remains depressed in recent years.

3. Sectoral Composition

The economy is classically structured in three sectors:

- Services: The dominant share, contributing more than 50 percent of GDP in earlier measures.

- Agriculture: Traditionally important — often around 20–25 percent of GDP and employing a large share of the rural population.

- Industry / Mining / Manufacturing: Smaller, constrained by infrastructure, capital scarcity, and security.

These proportions have fluctuated over time, with services (often informal) playing an outsize role relative to the weak industrial base.

4. Trade, Aid, and External Financing

- Afghanistan runs a large trade deficit. Historically, the country imported more than US$7 billion of goods while exporting only about US$784 million (pre-2021 figures).

- Key exports include fruits, nuts, carpets/rugs, and agricultural goods.

- After the Taliban takeover in August 2021, the U.S. froze approximately US$9 billion in Afghan central bank reserves.

- Foreign aid had been the backbone of government financing. Before 2021, donor grants funded a large share of public expenditure (for schools, health, salaries). The sharp curtailment of aid since 2021 has put severe pressure on the fiscal balance.

- The government has attempted to increase domestic revenue, particularly via customs and border duty collection, to partially offset the collapse in external support.

II. Structural Constraints & Risks

1. Landlocked and Mountainous Geography

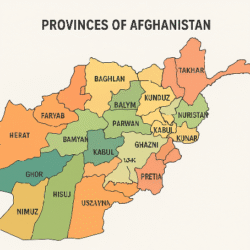

Afghanistan’s landlocked status forces dependence on neighbors (especially Pakistan) for access to seaports, increasing transport costs and border-related delays. Moreover, rugged terrain complicates infrastructure development (roads, rail, energy transmission). This limits economies of scale and raises the cost of business.

2. Conflict, Instability, and Security Risks

Persistent conflict undermines investor confidence, disrupts markets, and raises risk premiums. The Taliban government’s legitimacy remains contested internationally, curtailing access to many formal channels of development finance.

3. Governance, Institutional Weakness, and Capacity

Weak public institutions, corruption, lack of regulatory certainty, and limited capacity in customs, tax administration, and legal systems inhibit economic activity, especially formal private investment.

4. Financial Isolation & Capital Scarcity

- Afghanistan’s exclusion from much of the international banking system makes access to global capital markets highly constrained.

- The freezing of central bank reserves and limited access to foreign exchange reserves hampers monetary and fiscal maneuvering.

- Liquidity and credit in the domestic banking sector remain constrained; many transactions occur in informal or parallel financial systems.

5. Dependence on Aid & Vulnerability to External Shocks

The heavy reliance on donor funding made Afghanistan vulnerable to shifts in global aid priorities. Fluctuations in aid flows have outsized effects on public finances, social services, and macro stability.

6. Climate, Water, and Agriculture Risks

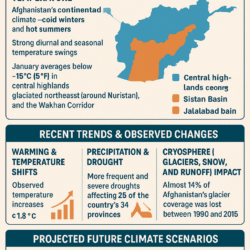

Afghanistan faces frequent droughts, erratic rainfall, glacial melt, and water scarcity — all of which threaten agricultural productivity. As agriculture underpins rural livelihoods, climatic shocks translate rapidly into food insecurity.

7. Human Capital, Gender Restrictions, and Labor Force

- The exclusion of women and girls from education and public life under Taliban rule erodes human capital, cuts labor supply, and undermines productivity over time.

- Skilled diaspora returnees were once a source of entrepreneurial dynamism; recent restrictions reduce that potential.

- Youth unemployment remains very high — new labor entrants (estimates ~400,000 annually) outpace job creation.

III. Recent Developments & 2025 Snapshot

1. Signs of Stabilization

- After several quarters of contraction, there are modest signs the economy is stabilizing.

- Inflation and deflation pressures have moderated: in 2024, deflationary conditions eased.

- Fiscal revenues (especially customs) have improved, enabling more regular — though still limited — salary payments to civil servants.

- One infrastructure development: in August 2025, the Pashdan Dam (in Herat Province) was inaugurated. The dam, built at a cost of about US$117 million, will serve both irrigation and power generation (≈2 MW) and irrigate adjacent farmland.

2. Negative Pressures and Crises

- Food insecurity and malnutrition are acute. In 2025, roughly 10 million people require food assistance; an estimated 3.5 million children are malnourished.

- The 2025 hunger crisis is among the most severe in recent years, with more than half the population in some classification requiring humanitarian aid.

- In September 2025, the Taliban ordered a nationwide internet shutdown, citing “morality” concerns, which severely disrupted communications, business, banking, and services.

- The suspension of U.S. aid in early 2025 further strained public services. It is estimated that US$1.7 billion in aid was cut off.

- Drought and environmental stress continue to degrade agricultural output.

- Many Afghan refugees and returnees (from Iran, Pakistan) add to the burden on local economies and humanitarian systems.

IV. Sectoral Outlook & Potential

1. Agriculture & Rural Development

Agriculture remains vital: not only for rural incomes but also for food security and export potential (e.g. nuts, fruits, saffron). However:

- Productivity is low due to limited irrigation, outdated farming techniques, lack of access to credit, and climatic instability.

- Infrastructure (roads, storage, cold chains) is weak, reducing the ability to access markets.

- Irrigation projects (like Pashdan Dam) and proposed dams like Bakhshabad (in Farah province) aim to expand water storage and usage capacity.

If agricultural reforms, microfinance expansion, and climate resilience measures are implemented, growth in rural incomes could be a stabilizing force.

2. Mining, Energy & Natural Resources

- Afghanistan is widely believed to hold vast mineral deposits (copper, lithium, rare earth elements, iron ore) worth perhaps trillions. However, actual exploitation is minimal due to security risk, lack of infrastructure, capital constraints, and unclear contractual and legal regimes.

- Energy is mostly hydropower and imports. The country currently generates ~600 MW internally, plus imports from neighboring countries.

- Projects like the CASA-1000 transmission line (linking Central Asian surplus electricity to Afghanistan and onward to Pakistan) are potentially transformative if completed.

- Regulatory reform, guarantees, and security are prerequisites to attract investment in mining/energy.

3. Services, Telecommunication, & Digital Economy

- Telecom investment prior to 2021 had been among the more successful sectors, employing tens of thousands.

- However, recent shutdowns, restrictions on internet access, censorship, and communications interruptions diminish confidence in a stable digital business environment.

- Financial services (banking, microfinance) are underdeveloped; much activity is informal.

- Tourism and cultural heritage remain largely untapped, given security concerns, but could become potential areas of growth with stabilization.

4. Construction & Infrastructure

- Reconstruction, road-building, housing, and public works historically drove growth (especially during international aid periods).

- With aid reduced, funding for large-scale infrastructure is constrained; private investment is low.

- Nonetheless small- to medium-scale building and local infrastructure still provide growth opportunities in urban and peri-urban areas.

V. Outlook, Scenarios & Strategic Imperatives

1. Growth Projections & Risks

- A baseline scenario: 2–3 percent annual growth in the near term (2025–2027), with slow improvements thereafter, contingent on some recovery in revenues, moderate international engagement, and relative political stability.

- Upside risks: Resumption of aid, foreign investment (especially energy/mining), improved regional connectivity, and reforms in governance or business climate.

- Downside risks: Further deterioration in security, deeper isolation, more draconian social restrictions, climatic shocks, and collapse in aid flows or inflation spikes.

2. Strategic Priorities

To move beyond stagnation, several structural reforms and strategies are vital:

- Institutional and Governance Reform

- Strengthening public finance management, tax and customs administration, transparency and rule of law will reduce barriers to private investment.

- Legal frameworks to attract foreign investment in mining, energy, and infrastructure must be credible and secure.

- Selective Infrastructure & Connectivity Investment

- Prioritize investments that unlock broad economic impact (roads, power, irrigation, border crossings).

- Regional transit corridors (Pakistan, Central Asia) must be leveraged to reduce isolation.

- Agricultural Productivity & Value Chain Development

- Expand irrigation, introduce modern farming practices, strengthen storage/transportation, facilitate access to inputs and credit.

- Develop agro-processing and value addition (e.g. nuts, dried fruits, saffron, horticulture) to increase export value.

- Mobilizing Domestic Revenues

- Expand tax base (including digital, property, income, trade) where feasible.

- Reduce leakage and corruption in customs and border revenue.

- Gradual Re-engagement of International Finance & Aid

- Even without full formal recognition, pragmatic arrangements (e.g. trust funds, restricted sectoral grants) can help restore critical services.

- Use external support strategically in infrastructure, human capital (health, education) and climate resilience.

- Promoting Inclusive Human Capital

- Reinstating access to education, especially for girls, is not just a moral imperative but an economic one.

- Vocational training, diaspora linkages, and small business support can enhance employment prospects.

- Crisis Management & Safety Nets

- Given persistent food insecurity, strengthening social protection programs, localized assistance, and emergency nutrition interventions is essential.

- Building resilience to climate shocks and internal displacement must be central to planning.

Afghanistan’s economic trajectory in 2025 is one of constrained recovery amid formidable structural, political, and humanitarian challenges. After the deep contraction post-2021, modest stabilization is emerging, yet the bounds of growth remain narrow. The country continues to struggle with trade deficits, limited formal investment, exclusion from financial systems, and acute social stress.

Ultimately, the gap between Afghanistan’s potential (given its natural resources and strategic location) and its actual performance is largely an institutional and geopolitical challenge, not a resource one. With selective reforms, pragmatic international engagement, and investments in human capital and connectivity, there is scope for gradual progress. But the path is perilous and uncertain: setbacks in governance, security, or climate shocks could easily unravel any fragile gains.

The coming years will be decisive in determining whether Afghanistan remains locked in low-income stagnation or begins a slow, fragile ascent toward recovery and sustainable development.