The Baka village of Bemba, located in South-Eastern Cameroon, is home to approximately 70 people and forms part of the wider Baka population of around 40,000. As one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer communities in Central Africa, the Baka have a deep spiritual and ecological connection to the rainforest, viewing it not only as their home but also as a benevolent parent and provider.

Despite the pressures of modernization, land disputes, and conservation efforts, the Baka of Bemba continue to uphold their traditions, mythology, and hunting practices, making their story one of resilience and cultural preservation.

Who Are the Baka People?

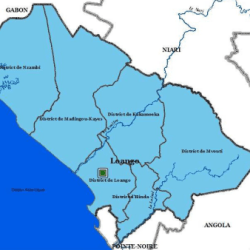

The Baka people are forest-dependent Indigenous people primarily found in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Gabon, and the Republic of Congo. Unlike the surrounding Bantu farming communities, the Baka have historically lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers, relying on the forest for food, medicine, and spiritual guidance.

Even though many Baka today live in permanent villages, their identity remains tied to their forest origins, and they continue to hold onto their myths, songs, and ecological wisdom.

The Village of Bemba – A Small but Resilient Community

Bemba is a small settlement located between the Dja River and the town of Mintom in Cameroon. Positioned along a logging track, the village is surrounded by a trophy hunting zone, a community forest, and two protected areas—the Ngoyla Wildlife Reserve and the Dja Biosphere Reserve.

The primary livelihoods of the Baka in Bemba include:

- Hunting and fishing in the surrounding forests and rivers

- Gathering of wild foods such as honey, nuts, mushrooms, and caterpillars

- Small-scale farming, though wild foods are considered more spiritually significant

- Providing traditional forest medicine to outsiders

Komba and the Baka’s Creation Myth

According to Baka mythology, Komba is the creator of the world and all living beings. The legend states that Komba first created the trees and the Baka, but when the Baka annoyed him, he cut them apart using a mystical knife, forming all other animals from their bodies. Later, he recreated the Baka from these cuttings, reinforcing their deep, inseparable connection to the forest.

The Baka also distinguish between bo na gba (village people) and bo na bele (forest people). Komba’s creation myth explains that the Bantu (Kaka) were meant to farm, while the Baka were meant to live in the forest, reinforcing their cultural identity even as many now reside in permanent settlements.

Kincentric Ecology – The Baka’s Relationship with the Forest

For the Baka, the forest is not just an environment—it is a parent that provides unconditionally. The anthropologist Jerome Lewis describes the Baka as “forest transformed into persons,” emphasizing their spiritual and physical dependence on their surroundings.

One Baka elder explains:

“In the forest, there is bark to heal you. So you see, the forest gives to us.”

Despite increasing reliance on agriculture, wild foods such as honey, yams, and game meat remain sacred, forming a direct connection to Komba and the ancestors.

The Concept of Mòkìlà – Shapeshifting and the Blurring of Human and Animal Forms

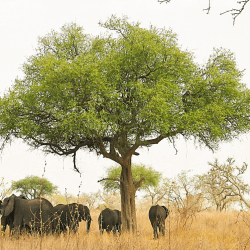

Among the Baka, powerful hunters known as tuma are believed to possess the ability to shapeshift (mòkìlà) into animals such as butterflies or elephants. This transformation is said to be enabled by a ritual sash (sìmbò) and a collection of sacred plant remedies (molombi).

While mòkìlà is often seen as a protective ability, allowing hunters to blend into the forest, other groups fear Baka shapeshifters, believing them to be sorcerers with the power to attack or trick people.

Though fewer Baka practice mòkìlà today due to modernization and a decline in elephant populations, stories of shapeshifting hunters escaping danger remain a crucial part of Baka oral tradition.

The Spirits of the Forest – Mē and Their Role in Baka Culture

The Baka believe in powerful forest spirits known as mē, who live in camps and share a love for the same wild foods as the Baka. These spirits are occasionally invited into villages during spirit-play ceremonies (bé), which involve:

- Ritual songs sung by women to summon the spirits

- Elaborate dances performed by the spirits

- Offerings of food and game to appease the spirits

One of the most important spirits is Ejengi, known for bringing protection and healing to the community. If the songs or offerings are insufficient, the spirit may refuse to enter the village and return to the forest instead.

FAQs About the Baka People

1. What language do the Baka speak?

The Baka primarily speak the Baka language, a Bantu-related dialect, though many also understand French or other regional languages.

2. How do the Baka hunt?

They use bows, spears, traps, and hunting dogs, along with rituals and songs to attract game.

3. What role do spirits play in Baka life?

Spirits provide protection, healing, and guidance through rituals and ceremonies.

4. How do the Baka view the forest?

The forest is seen as a parent that provides unconditionally, ensuring their physical and spiritual well-being.