1. Genetic Classification

Chinese belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family, within the Sinitic branch. Many scholars argue that all forms of Chinese constitute an independent sub-family of Sino-Tibetan, coordinate with Tibeto-Burman, the other major branch of the family. This classification, however, is not universally accepted. Some linguists instead propose that Chinese varieties form a separate language family, distinct from Tibeto-Burman altogether.

2. Chinese Language

Chinese is the most widely spoken language in the world, used by nearly 20 percent of the global population. It also has the longest continuous written tradition of any living language, spanning approximately 3,200 years.

Typologically, Chinese is a tonal and isolating language. In its earliest stages, it was almost entirely monosyllabic, but Modern Chinese contains many disyllabic and trisyllabic words. Morphemes are largely invariable, each encoding a single lexical or grammatical meaning, and they combine without inflection.

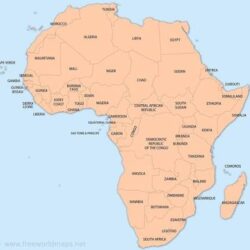

3. Geographic Distribution

The vast majority of Chinese speakers live in China, including Hong Kong and Macau, and Taiwan. Significant Chinese-speaking communities exist worldwide due to migration, particularly in:

- Southeast Asia: Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia, the Philippines

- East Asia: South Korea, Japan

- North America: United States, Canada

- South America: Peru, Brazil, Argentina

- Oceania: Australia

- Africa: South Africa

4. Number of Speakers

Including all dialects, Chinese has approximately 1.3 billion native speakers. Major concentrations (in millions) include:

| Country | Speakers |

|---|---|

| China | 1,220.0 |

| Taiwan | 22.6 |

| Malaysia | 6.5 |

| Indonesia | 3.0 |

| USA | 2.8 |

| Singapore | 2.5 |

| Thailand | 2.0 |

| Myanmar | 1.1 |

| Vietnam | 1.0 |

| Canada | 1.0 |

| Philippines | 0.9 |

| Australia | 0.5 |

| South Africa | 0.2 |

5. Dialect Groups

Chinese dialects share a large core vocabulary but differ substantially in phonology. Seven major dialect groups are generally recognized:

- Mandarin (70%) – Northern and Southwestern China

- Wu (8.5%) – Zhejiang, southern Jiangsu, Shanghai

- Yue (Cantonese) (5.5%) – Guangdong and neighboring areas

- Min (4.5%) – Fujian, Taiwan, Hainan

- Hakka (Kejia) (4%) – Northeastern Guangdong

- Gan (2.5%) – Jiangxi

- Xiang (5%) – Hunan

Mandarin itself consists of several varieties, broadly grouped into Northern, Northwestern, and Southwestern dialects. Standard Chinese is based on the Beijing dialect, though it incorporates vocabulary from other Mandarin varieties.

6. Sociolinguistic Status

Modern Standard Chinese, officially known as Putonghua, is the national language of China and the medium of instruction and mass media. It is also an official language of Taiwan, Singapore, and one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

7. Historical Periods of Chinese

7.1 Proto-Chinese (1200–771 BCE)

The earliest records are oracle-bone inscriptions and bronze inscriptions. Roughly 4,000 characters have been identified, though only about half have been deciphered.

7.2 Old Chinese (771 BCE–220 CE)

Beginning with the Zhou dynasty, this period includes early literary works such as the Book of Songs. Han dynasty dictionaries provide crucial phonological insights.

7.3 Middle Chinese (220–960 CE)

Characterized by political fragmentation and later reunification. Rhyme dictionaries such as the Qièyùn are key sources for reconstructing pronunciation.

7.4 Early Modern Chinese (960–1900 CE)

Rhyme books like Zhōngyuán Yīnyùn and Hóngwǔ zhèngyùn inform phonological reconstruction. European missionaries produced the first Latin transcriptions.

7.5 Modern Chinese (1900–present)

Standardization of characters and pronunciation occurred, and Pinyin was officially adopted in 1956.

8. Earliest Written Evidence

The oldest Chinese texts appear on:

- Oracle bones (turtle shells and ox scapulae) used for divination

- Bronze vessel inscriptions from the Shang and Western Zhou periods

9. Phonology

9.1 Syllable Structure

Each syllable contains a vowel nucleus, possibly forming diphthongs or triphthongs. Consonant clusters are disallowed. Mandarin permits only -n and -ŋ as final consonants, while Cantonese allows -m, -p, -t, -k as well.

9.2 Vowels and Consonants

Mandarin has seven vowels and approximately twenty-two consonants. Stops and affricates are voiceless with aspirated vs. unaspirated contrasts.

9.3 Tones

All Chinese dialects are tonal. Mandarin has four lexical tones plus a neutral tone. Tone sandhi occurs when syllables combine in connected speech.

10. Writing System

Chinese is a logographic writing system, with each character representing a syllable and lexical unit. Major historical stages include:

- Oracle-bone script

- Bronze script

- Seal script

- Standard script

- Simplified Standard script (since 1965)

11. Romanization and Orthography

Pinyin represents Chinese sounds using the Latin alphabet, with systematic conventions for aspiration, affricates, fricatives, vowels, and tone marking.

12. Morphology

Chinese morphology is isolating, with no inflection for case, gender, tense, or mood. Grammatical relations are expressed through word order, particles, and classifiers.

Key features include:

- Pronouns and demonstratives

- Possessive, relative, and adverbial particle de

- Sentence-final particles (ma, ne, ba, a/ya)

- Aspect markers (-le, -guo, -zhe)

- Plural marker -men

Word formation occurs through compounding, derivational affixing, and reduplication.

13. Syntax

Chinese syntax relies heavily on word order, typically Subject–Verb–Object. Topic-comment structures are common, and the copula is often omitted. Serial verb constructions and classifier-based noun phrases are characteristic.

14. Lexicon

Chinese vocabulary reflects centuries of contact with other cultures, incorporating loanwords from Sanskrit, Japanese, Mongolian, European languages, and, more recently, English, especially in technical and scientific domains.

15. Literary Tradition

Chinese literature spans over three millennia, from early classics such as the Shijing and Daodejing to major novels like Journey to the West and Dream of the Red Chamber, and modern works by authors such as Lu Xun, Mao Dun, and Lao She.