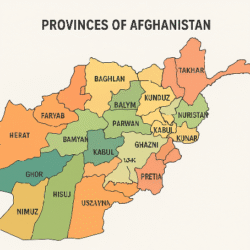

Afghanistan’s climate is highly diverse and strongly influenced by its complex topography. The country encompasses high mountain ranges (such as the Hindu Kush and Pamirs), plateaus, and low-lying basins. This leads to large spatial and seasonal variation in temperature, precipitation, and climate-change impacts. Below is a detailed, up-to-date summary of Afghanistan’s climate, recent trends, and the key risks facing the country as it confronts climate change.

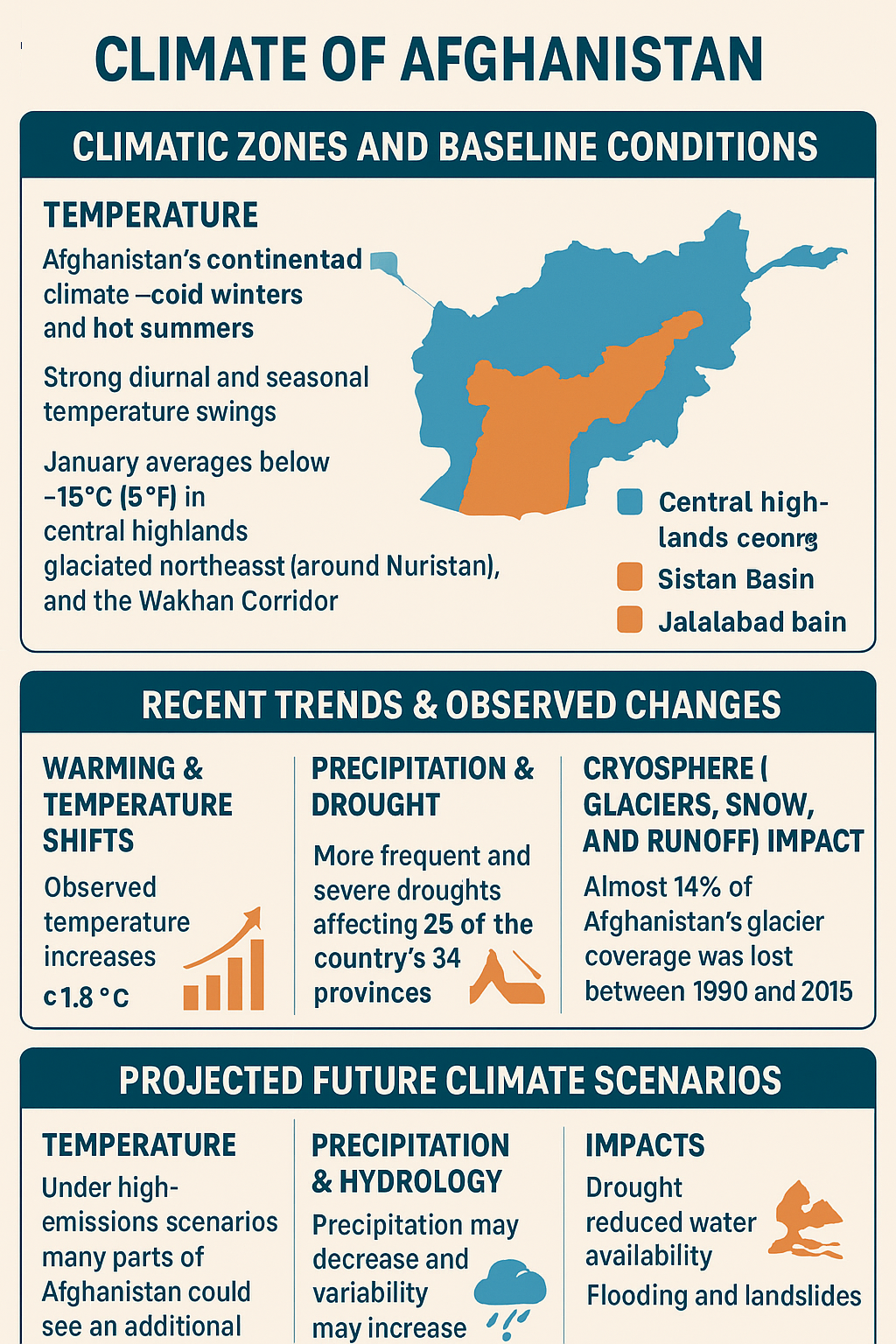

1. Climatic Zones and Baseline Conditions

Temperature Regimes

- Afghanistan experiences a continental climate in many regions: cold winters and hot summers, with strong diurnal and seasonal temperature swings.

- In winter (January), mean temperatures in cold interior mountain zones may drop well below freezing, while in summer (July) many lowland areas exceed 30 °C or more.

- In Kabul, for example, January average is about 1.5 °C, while July averages can reach ~26.8 °C, and peak summer temperatures can exceed 40 °C.

- In Kandahar (a lower-altitude southern region), the annual average temperature is ~20.1 °C, with very hot summers.

- In Panjab (in the high-altitude Bamyan region), the climate is humid continental (or close to subarctic), with a January average of –8.7 °C and July average ~15.7 °C.

- On the national scale, over the period 1901–2023, Afghanistan’s average temperature has hovered around 12.7 °C.

- Recent extremes are notable: in January 2023, a devastating cold snap saw temperatures drop as low as –33 °C in high mountain areas, resulting in hundreds of human and livestock fatalities.

Precipitation Patterns

- Annual precipitation is highly variable spatially, depending largely on elevation, exposure to prevailing wind systems, and rain shadows.

- Low-lying southwestern and western regions may receive less than 150 mm of precipitation annually.

- In contrast, some high-elevation areas in the northeast receive over 1,000 mm annually.

- National averages often cited are in the range of ~250–320 mm/year, though these are rough and can mask extreme variation.

- In Kabul, precipitation is modest (~300 mm/year), mostly concentrated in the late winter to spring months; summer is very dry.

- Precipitation in Afghanistan shows pronounced seasonality: most falls from December through April, with very little during the summer months in many regions.

- Afghanistan lies largely outside the Indian monsoon influence, except in eastern provinces such as Nuristan, which occasionally receive summer monsoon rainfall.

2. Recent Trends & Observed Changes (Last Few Decades)

Warming and Temperature Shifts

- Afghanistan has warmed more than many other regions. Since about 1950, observed temperature increases of ~1.8 °C have been reported.

- The increase tends to be more pronounced in minimum (nighttime) temperatures than in maxima, reducing diurnal temperature range in many places.

- In 2023, Afghanistan recorded one of its highest average national temperatures (~14.61 °C), a new record for the country.

Changes in Precipitation and Drought

- Some river basins, like that of the Kunduz River, have experienced ~30% reductions in precipitation relative to past decades.

- Severe drought conditions now affect 25 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, impacting more than half the population.

- The country is currently enduring its worst drought in about 30 years, with reported rainfall amounts less than half of average in some regions.

- Because of warming, evaporation rates have increased, placing greater stress on soils, water bodies, and vegetation.

Cryosphere (Glaciers, Snow, and Runoff) Impact

- Between 1990 and 2015, Afghanistan lost nearly 14% of its glacier coverage.

- Projections for the Hindu Kush–Himalayan region indicate that by 2100, up to 60% of glacier mass in some parts could be lost under continued warming.

- Declining glaciers and snowmelt reduce late-season runoff, which many downstream communities rely on.

- The risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) is increasing, especially in mountainous valleys with newly formed glacial lakes.

Extreme Events & Variability

- Patterns of intense rainfall over short durations have become more frequent, aggravating flooding and landslides risks.

- In 2023, a cold snap killed at least 160 people and 77,000 livestock in mountainous regions.

- Recently (2025), heavy precipitation and sudden snowfalls have caused fatalities and infrastructure damage in multiple provinces.

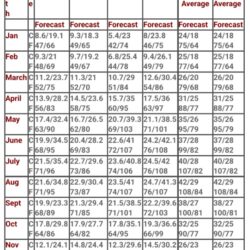

- The Climate Prediction Center’s short-term outlooks (monthly/seasonal) often note temperature anomalies (±1–4 °C) and forecast regions of enhanced or suppressed precipitation.

3. Projected Future Climate Scenarios

Temperature Projections

- According to climate-change modeling, Afghanistan’s warming is expected to exceed the global average.

- Under high-emissions scenarios, many parts of the country could see an additional 2–4 °C increase in mean temperature by mid- to late 21st century.

- Increases in minimum temperatures (nighttime warming) may be particularly steep, which can affect snow retention, soil moisture, and ecological stress.

Precipitation & Hydrology

- Projections of precipitation changes are more uncertain, but many models suggest less winter precipitation in some basins, and increased variability (heavier rainfall in some episodes, longer dry spells).

- Shifts in snow/rain partitioning: more precipitation may fall as rain rather than snow in mid-elevations, reducing snowpack and altering timing of runoff.

- Glacial retreat will further hamper long-term water yield from high-elevation zones, affecting downstream water availability.

Impacts on Water Availability

- Many groundwater aquifers, particularly around urban centers (e.g. Kabul), are being over-exploited. The recharge is not keeping pace with abstraction, especially under declining precipitation and glacier melt.

- In fact, reports warn that Kabul could run out of water by 2030 if current trends continue.

4. Impacts Across Sectors & Vulnerabilities

Agriculture, Food Security & Livelihoods

- Droughts and inconsistent rainfall severely affect crop yields, especially in rainfed farming zones.

- As of 2025, over 10 million people in Afghanistan face acute food insecurity, worsened in part by climate shocks.

- Child malnutrition is rising rapidly; one in three children is stunted, in part from climate-driven agricultural losses.

Water Security & Access

- Many rural and urban areas already depend on shallow wells, boreholes, and small reservoirs, which are under stress.

- The overuse of groundwater in cities, combined with declining recharge, undermines long-term supply sustainability.

Human Displacement & Migration

- Climate stress is a major factor in internal displacement, especially when drought destroys livelihoods or floods damage infrastructure.

- By 2050, climate-driven displacement estimates suggest up to 5 million additional internally displaced persons.

Natural Hazards

- More frequent and intense floods, landslides, and glacial lake outbursts pose risks to communities in mountainous zones.

- Cold extremes, such as sudden cold snaps, continue to cause loss of life and livestock in high-altitude regions.

Health & Livelihood Stress

- Heat stress, water scarcity, crop failures, and malnutrition interact to raise public health risks, especially among vulnerable populations.

- In conflict-affected areas, climate pressures combine with socioeconomic fragility, compounding vulnerability.

5. Challenges to Adaptation & Resilience

- Institutional Constraints: Weak governance, political instability, and limited capacity impede planning, coordination, and investment in climate adaptation.

- Resource Limitations: Financial, technological, and human resources are scarce, especially under current international sanctions and aid constraints.

- Data Gaps: Observational networks (weather stations, stream gauges, glacial monitoring) are sparse in remote and mountainous areas, making high-resolution projections and early-warning systems difficult.

- Infrastructure Vulnerabilities: Many roads, irrigation systems, and water storage facilities are fragile and poorly maintained, reducing their resilience to floods or droughts.

- Social Equity Issues: Women, children, internally displaced persons, and marginalized communities are disproportionately affected by climate impacts, but may lack voice or access to resources.

6. Outlook & Key Takeaways

- Afghanistan’s climate is already shifting: warming, intensifying droughts, increasing variability, and retreating glaciers are no longer distant prospects but ongoing realities.

- The intersection of climate stress with political, economic, and social fragility makes the country exceptionally vulnerable.

- Without significant investment in climate adaptation—ranging from water management and drought-resistant agriculture to early warning systems and infrastructure resilience—many Afghan communities face deepening hardship.

- Mitigation (i.e. reducing emissions) is less relevant in the Afghanistan context because the country’s emissions are very low globally. The priority is adaptive resilience, humanitarian preparedness, and sustainable development strategies.