Afghanistan occupies a pivotal place in the geographic and climatic mosaic of Central and South Asia. Its landscapes and weather patterns are remarkably varied, shaped by towering mountains, deep river valleys, arid basins, and climatic forces that range from continental extremes to monsoonal fringes. This article offers a detailed and up-to-date overview of Afghanistan’s geography, climate zones, environmental challenges, and the broader significance of its terrain in regional processes.

1. Geographic Setting & Borders

1.1 Location and Area

- Afghanistan is a landlocked country in South-Central Asia, often described as part of Central Asia due to its geographic and cultural connections.

- Its total area is approximately 652,000 to 652,864 km² (some sources round this to ~647,000 km²) — placing it roughly between the sizes of France and Myanmar.

- The country is sometimes called the “Heart of Asia” owing to its historic role as a crossroads linking Central, South, and West Asia.

1.2 Borders

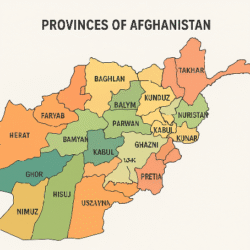

Afghanistan shares boundaries with six countries:

- Pakistan: To the east and south, separated by the Durand Line, a boundary with historical and contemporary tensions.

- Iran: To the west.

- Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan: To the north & north-west.

- China: A small border in the far northeast (in the Wakhan Corridor, connecting to China’s Xinjiang).

Because Afghanistan is landlocked, it has no coastline.

1.3 Physiographic Regions

Afghanistan’s topography can broadly be divided into three major zones:

- Northern plains / river valleys

- These low-lying areas lie north of the major mountain ranges and include parts of the Turkestan plains.

- They are among the most fertile zones and carry much of the country’s agriculture.

- Central highlands / mountain core

- Dominated by the Hindu Kush mountain system, which trends northeast to southwest, and linking into the Pamirs, Karakoram, and Himalayan ranges.

- About two-thirds of the country’s land area lies above 2,000 m (≈ 6,500 ft) in elevation.

- Steep ridges, deep valleys, narrow gorges, and glaciated peaks are characteristic.

- Southern & southwestern plateau and desert regions

- Beyond the high mountains toward the south and southwest, the terrain falls into drier plateaus, semi-arid basins, and desert landscapes (such as the Registan Desert).

- Much of this region is sparsely populated and agriculturally marginal.

Within these zones, narrow river valleys and irrigated corridors provide the main habitable and cultivable areas.

1.4 Key Topographic Features & Highlights

- The highest point in Afghanistan is Noshaq (Nowshak) at about 7,492 m (roughly 24,580 ft).

- The lowest point lies in the Jowzjan Province along the Amu Darya river bank, about 258 m (846 ft) above sea level.

- The Registan Desert lies between Helmand and Kandahar provinces in the southeast, characterized by sand dunes, clay plains, and very low moisture.

- Band-e Amir National Park, located northwest of Bamyan, is a scenic high-altitude lake system in the Hazarajat region. The six lakes are formed by natural travertine dams, making it among Afghanistan’s most famous natural sites.

- The Wakhan Corridor, in the far northeast, is a narrow stretch of land connecting Afghanistan to China, tucked among high mountains (Pamir region).

2. Climate & Hydrography

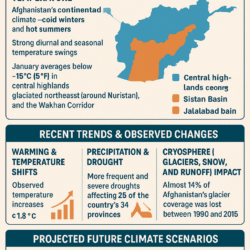

2.1 General Climate Regime

- Afghanistan’s prevailing climate is continental and arid to semi-arid.

- Because of its rugged topography and altitude gradients, temperature and precipitation vary strongly across seasons and elevations.

- The country receives very high solar radiation (often above 3,000 hours of sunshine annually in many locales) combined with low relative humidity.

- Evaporation rates are high, further limiting water retention in soils and surface water bodies.

2.2 Temperature Patterns

- In the winter months (December to February), average minimum temperatures often fall below freezing in many regions. In high mountain areas, extremes can go well below –20 °C; in the central highlands and northeastern zones, January averages may drop below –15 °C.

- In summer (June to August), the lowland and basin areas can become extremely hot: temperatures over 35 °C are common, and some regions (such as the Sistan Basin, Jalalabad basin, northern plains) can exceed 43 °C.

- In high mountainous zones, the peaks and passes can remain cold even in summer and have wide diurnal (day–night) temperature swings.

2.3 Precipitation & Seasonal Patterns

- Annual rainfall (or effective precipitation) is modest, often averaging around 250 to 337 mm in many regions, though this varies widely by elevation and location.

- In the higher altitudes (northeast, mountain zones), precipitation can be higher (up to 1,200 mm in some pockets), often falling as snow in winter.

- The rainy (and snowy) season is concentrated in winter through early spring (December to April). In many parts, March–April sees peak moisture input.

- In the extreme north and northeast, there is some monsoon influence in limited sectors (e.g., Nuristan province), though the bulk of Afghanistan lies outside the monsoon zone.

- The dry season (late spring through summer into early autumn) typically sees minimal rainfall; many lowland and desert areas may receive only sporadic storms.

2.4 River Systems, Glaciers & Water Flow

- Afghanistan contains numerous rivers and headwaters that feed into regional river systems. Major rivers include the Amu Darya, Kabul River, Helmand River, Hari River, and Arghandab among others.

- Snowmelt and glacial melt from the mountain zones are critical sources of water during the spring and early summer, sustaining river flow when precipitation is low.

- Many hydrological basins are endorheic or semi-closed (e.g., the Sistan Basin), meaning water does not always flow to the ocean but may evaporate or seep into the ground.

- Runoff is limited, and large parts of the country are water stressed—two-thirds of Afghanistan’s water is reported to flow into neighboring states (Iran, Pakistan, Turkmenistan) via transboundary river systems.

3. Land Cover, Vegetation & Ecological Challenges

3.1 Land Cover & Use

- Rangeland / grassland covers a significant share of Afghanistan’s land, particularly in the northern and eastern zones. In 2018, rangeland accounted for about 44.6% of land area.

- Barren land / bare and rocky terrain is another large category, especially in central and southern zones. In 2018, barren land comprised ~34.8% of the land area.

- Irrigated agricultural land is relatively limited but has increased slightly (from ~2.81% in 2000 to ~3.30% in 2018).

- Forest cover is very low: about 1–2% of the total land area. There has been negligible primary forest, and much of the forested area is under public ownership.

3.2 Vegetation Types & Biomes

- In the mountain zones, coniferous forests (pines, firs), junipers, walnuts, almonds, and other native species are present, often in protected valleys or cooler slopes.

- At higher altitudes, alpine and tundra vegetation may hold at cold limits.

- In the lowland and arid zones, steppe, shrubland, desert scrub, and sparse grasses dominate.

3.3 Environmental & Ecological Challenges

Afghanistan is under significant ecological stress due to a combination of natural and human pressures:

- Deforestation and forest degradation: Over past decades, many forests have been lost for fuelwood, timber extraction, agriculture, and war-related disruption.

- Drought and desertification: Some 75% of the land in northern, western, and southern regions has been affected by desertification processes.

- Glacial retreat: Between 1990 and 2015, ~14% of glacier cover was lost, heightening the risk of glacial-lake outburst floods (GLOFs) in alpine zones.

- Climate change amplifiers: Warming trends (1.8 °C since 1950) are projected to intensify droughts, floods, and water stress.

- Water scarcity and aquifer depletion: Kabul, for instance, faces a critical water crisis, with aquifer levels dropping precipitously.

- Disasters (earthquakes, floods, avalanches): Afghanistan is seismically active. Recent earthquakes (e.g. 2023 magnitude 6.3 near Herat), severe cold snaps (2023 saw temperatures as low as –33 °C), and flash floods have caused significant human and infrastructural damage.

4. Climate Change Vulnerabilities & Future Projections

4.1 Temperature & Precipitation Trends

- Afghanistan is expected to experience warming greater than the global average, with both daytime highs and nighttime lows rising steadily.

- Seasonal precipitation patterns may shift; increases in extreme rainfall (leading to floods) and more frequent drought episodes are anticipated.

4.2 Glacier Loss & Hydrological Risk

- Under climate projections, the Hindu Kush–Karakoram–Himalaya (HKH) region may lose a majority of its glacial mass by 2100, threatening water security in downstream systems.

- Disruption in snowmelt timing and volume can stress river flows, impair irrigation systems, and amplify conflicts over water resources.

4.3 Human & Agricultural Impacts

- Over half of Afghanistan’s provinces are already affected by severe droughts, impacting livelihoods, food security, and internal displacement.

- In 2025, Afghanistan faces one of its worst hunger crises, with millions suffering from acute food insecurity — a crisis worsened by climate shocks, economic collapse, and funding cuts.

- The urban water crisis, especially in Kabul, is acute. The capital may run out of sustainable water supply by 2030 if current extraction and recharge imbalances continue.

5. Strategic & Regional Importance of Afghanistan’s Geography

5.1 A Geographical Crossroads

Afghanistan’s location at the confluence of South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East gives it strategic importance for trade, cultural exchange, and geopolitics. Its mountainous terrain has historically served as both a barrier and a corridor.

5.2 Water and Transboundary Hydrology

Rivers originating in Afghanistan contribute to regional water systems (e.g., Amu Darya, Kabul → Indus). This places Afghanistan in key roles vis-à-vis water security, treaties, and regional cooperation.

5.3 Natural Hazards & Infrastructure Constraints

Its rugged terrain complicates infrastructure development (roads, power lines) and makes many zones vulnerable to landslides, avalanches, seismic events, and flash flooding.

5.4 Environmental Pressures & Social Stability

Environmental degradation, water stress, and climate impacts act as threat multipliers, contributing to food insecurity, migration, and conflict risk. The complex geography intensifies these pressures.

6. Summary & Outlook

Afghanistan’s geography is defined by extremes: enormous altitude ranges, steep mountain complexes, narrow fertile valleys, and vast arid plateaus. Its climate is equally extreme — scorching summers in lowlands and bitter winters at high elevations, punctuated by scarce but seasonally concentrated precipitation. The country’s ecological vulnerabilities (forest loss, desertification, glacier retreat, water scarcity) are magnified by ongoing and future climate shifts.

Looking ahead:

- Water security will be a central challenge, especially in urban centers like Kabul.

- Climate adaptation is essential: improved irrigation efficiency, watershed management, reforestation, and resilient infrastructure.

- Regional cooperation over transboundary water, disaster response, and sustainable development will become ever more critical.

- Disaster risk reduction measures for earthquakes, floods, and cold extremes must be prioritized, especially in remote mountainous zones.

Afghanistan’s rugged landscapes and climatic complexity are a double-edged sword — they confer strategic depth, but also impose formidable constraints on development, resilience, and sustainability.