Igbo traditional houses and whole villages were built without predesigned plans. They evolved as a result of local conditions.

The winding streets and lanes of the villages were adapted to the positions of separate compounds, which were usually erected according to the choice of each family at a distance from and quite independently of the neighborhood

The debating ground (ilo) was used for important meetings, public discussions and settlement of differences between individuals or households.

Water supply

The location of Igbo villages was not determined by the proximity of water supply, except for those villages actually situated on stream banks, there were many far away from any source of water- which had to be carried for domestic purposes by the women.

During the rainy seasons, water was gathered in dug- out catch pits or by an elaborate system for collecting water from the pitched roofs of the buildings.

Compounds

There were those with rectangular plan, in which the entrance gate defined the longitudinal axis, on which the chiefs house was usually erected, as in Emene Owo, or Ukehe.

There were furthermore, strikingly different plans in the Ngwo areas, where family settlements were laid out at considerable distance from each other.

This permitted a compound design which could be roughly inscribed within a triangle, with the entrance gate at the sharp point, the side walls extending sharply outwards and again with the chiefs house on the longitudinal axis; the other buildings were scattered around. In some cases, the two principles of composition were combined, forming a blend, creating a symmetry and organized life within the outer boundary wall in an orderly, functional scheme.

Buildings

The variety of design in Igbo buildings was greater than that in the design of compounds.

This was a natural consequence of the diversity of the materials used for the wall, roof construction and decoration.

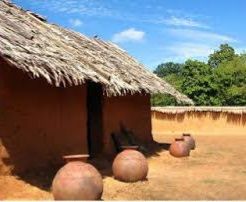

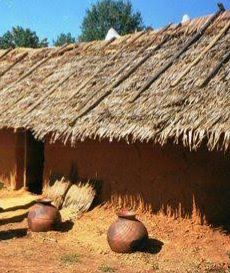

Only a few architectural features can be accepted as typical for the whole region: the rectangular plan of dwellings, which were without windows, the verandahs in front of the houses and the almost universal use of forked posts to carry the roofs.

Apart from dwellings other common features of Igbo buildings were: massive compound gates, meeting houses (for families, patrilineages and secret societies); shrines and (nowadays almost non- existent), two or three storeyed semi- defensive buildings known as Obuna Enu.

Each master of a family has a large square piece of ground, surrounded with a fence or enclosed with a wall made of red earth tempered, which when dry, is as hard as brick.

In the middle stands the principal building appropriated to the sole use of the master and consisting of two apartments, in one of which he sits with his family and the other left for the reception of his friends.

Besides this, he has a distinct apartment in which he sleeps with his male children.

On each side are the apartments of the wives, who have separate day and night houses.

These houses never exceed on store in height; they are always built of wood or stakes driven into the floor, crossed with wattles and neatly plastered within and without.

The roof is thatched with reeds, day houses are left open while those for which people sleep are covered and plastered in the inside with a composition mixed with cow dung to keep off different insects which cause disturbance at night.

Walls and floors are generally covered with mats and the beds consists of a platform raised three or four feet from the ground on which are laid skins and different parts of a spungy tree named plantain.

The structures of Igbo walls depended on the quality of the building earth available in the area.

Two different techniques were used in building walls. They were either erected in thick, solid layers of processed loam, or made using the wattle and daub method.

Loam walls were usually built on foundations (ogugu) which varied in depth from 15 up to 45 centimeters and thickness corresponding with that of the walls.

Walls were organically connected with the roofs, using forked posts to carry and support the roofs, set in various ways into the walls.

The wattle and daub system was quite widespread, which consisted of a number of vertical rods at approximately 15 centimeter centers, with three stronger forked posts supporting the roofs at the ridge and at the edges.

The standard element of Igbo roof construction was the forked post, for which many species of plants used, in many sizes and in a variety of natural shapes or decorative elaborations, usually set in the ground on rectangular bases of loam and on top of walls.

In Enugu, important houses consists of three spaces, an open verandah and two parallel interiors, only the front of the verandah is furnished with low forked posts and purlins.

The remaining part of the rafters is carried on the two longitudinal partition walls and on the back wall of the building.

Each of these is suitably adapted in height. Some rectangular buildings were enlarged by ellipsoidal verandahs and the roof covering the whole was conically shaped.

Built only in multi- storeyed buildings (obuna- enu meaning upper floor). The upper floors mostly provided a storage space and occasionally used for sleeping and a place of refuge for women and children when the men were at war.

Accesses to upper floors were by means of ladders. They were built of clay, for protection against burglars and fires.

Doors made of single, massive plank produced by chipping whole trunks of wood, usually iroko, from both sides until the desired thickness is achieved.

They are of various sizes from very small, to the normal sizes used in residential houses and occasionally larger doors in the gates of compound walls.

Building Materials

LOAM: This is the product of processing building earth, which varies considerably in quality in Igbo speaking tribes, ranging from the best- red, claylike and viscous to grayish soil which is not strong enough to be used without an inner reinforcement of wattle.

Loam walls used in an overlapping form or order

Earth is usually dug around the middle of the wet season from pits near the building site, with removal of the topsoil which exposes the red clay beneath. This is broken into small lumps with hoes and left in the pit until the rains come. More water is let into the hole by channels created in the surrounding ground. When the clods are wetted sufficiently, workers puddle them with their feet, adding more clay or water as necessary until the mixture attained is of the desired density and plasticity. Loam is occasionally prepared by mixing together different materials such as common earth which contained fine gravel and was strengthened by the addition of high quality clay (ngwa) brought from specially chosen pits.

TIMBER: Almost over the whole country and found in Enugu, the Oil palm (Elaesis guineensis) grows abundantly. Its trunk is composed of fiber, which is a poor building material but when split; can be used for rafters and purlines, and occasionally for posts. Ropes from the mid- ribs of the frond are mainly used for lashing the framework for wattle and daub walls. Real Bamboo (species Bambusa and Oxytenantha) grows in the Enugu area and to the north of it. It grows in clusters and reaches up to 15meters in height and 12 centimeters in diameter. They are mostly used for roof construction. Timber used in composite pillars

ROOF THATCHING- MATS: the favored species of fronds were from the ngwaw palm (Raphia vinifera).

Sometimes the fronds are laid horizontally along the roof with their midribs nearly touching each other. The other method, though laborious but superior, was achieved by making rectangular panels, sometimes called bamboo mats (akanya or atani).

Making mats out of palm fronds

ROOF THATCHING GRASS: Grass (akirika) for thatching was called ejo. In the process of preparing the grass for thatching, two kinds of strings are used: eriri and ekwere. Both are made from same thin strips of green skin torn off the midribs of nkwu palm fronds (iku- nkwu).